This article was originally published on Atlanta Business Chronicle on August 19, 2022.

Cancer is the second-leading cause of death in the United States, with more than 600,000 people dying of cancer in the country in 2021. While the U.S. death rate, or the percentage of people dying from cancer, is decreasing — partly due to fewer people smoking — the number of cancer deaths is going up due to our aging population. All these statistics are behind the call to decrease cancer deaths by 50% in the next 25 years. Atlanta Business Chronicle recently talked with a panel of experts from Wellstar Health System and the American Cancer Society, headquartered in Atlanta, about ways to accelerate cancer care progress through scientific research, patient care, partnerships, early detection, diversity and inclusion, and local care.* (Remarks edited for clarity and brevity.)

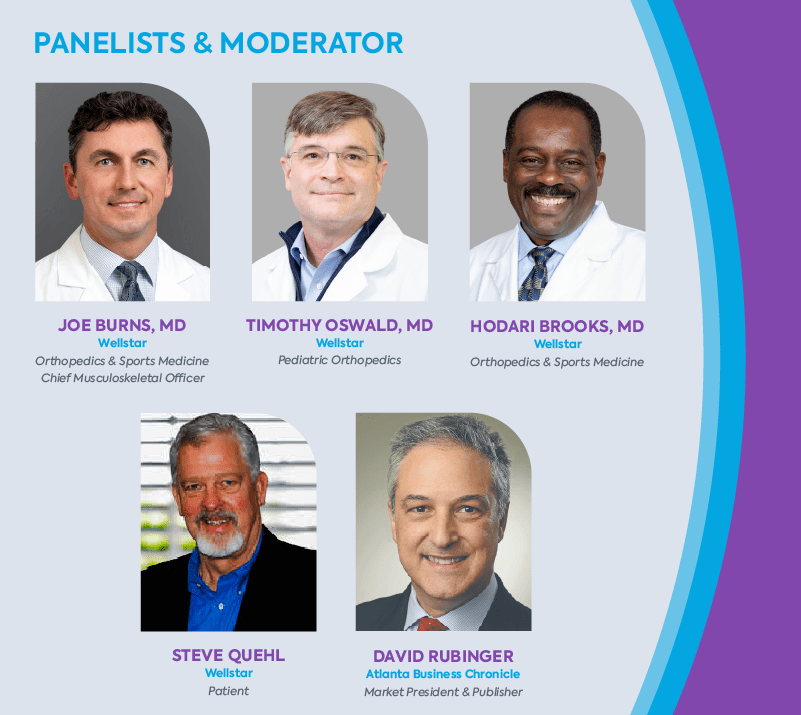

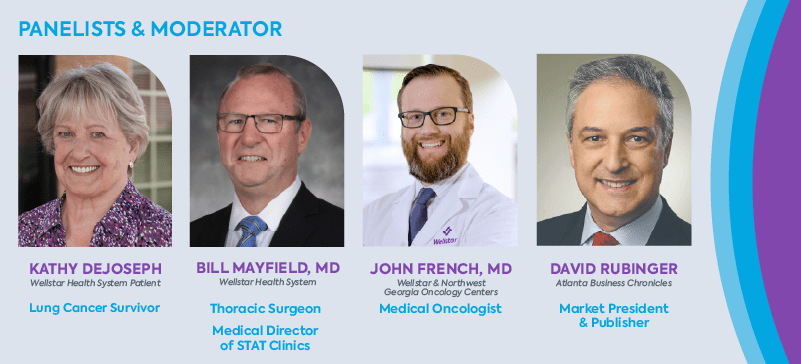

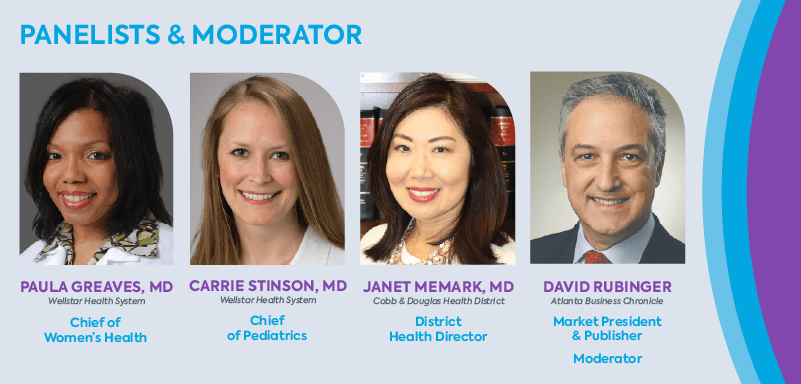

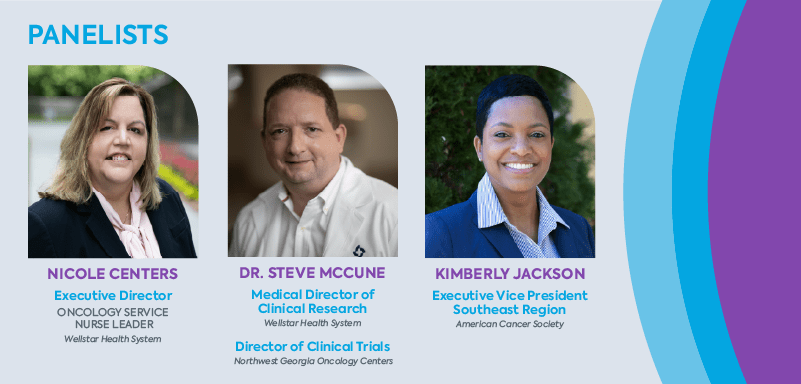

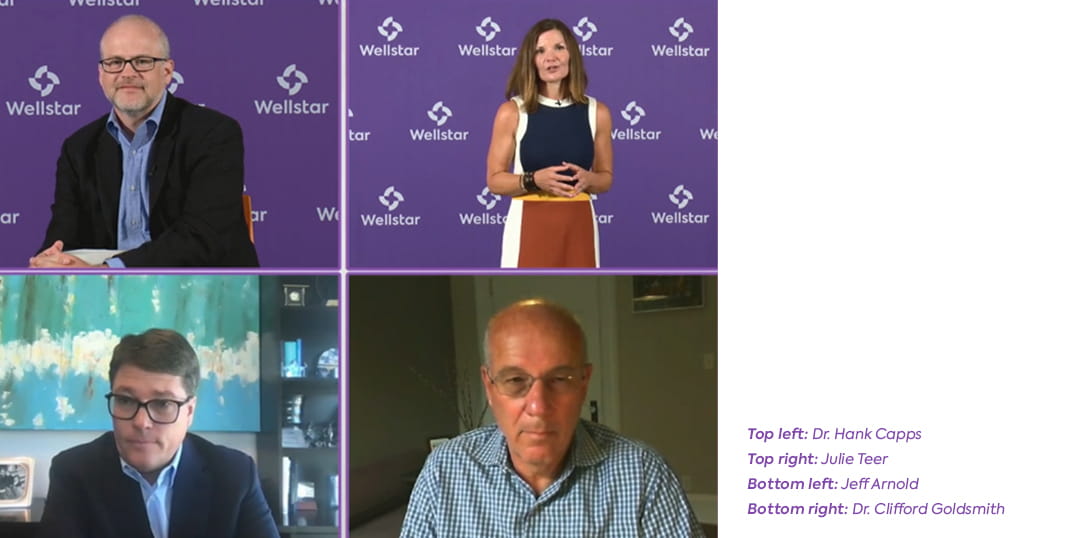

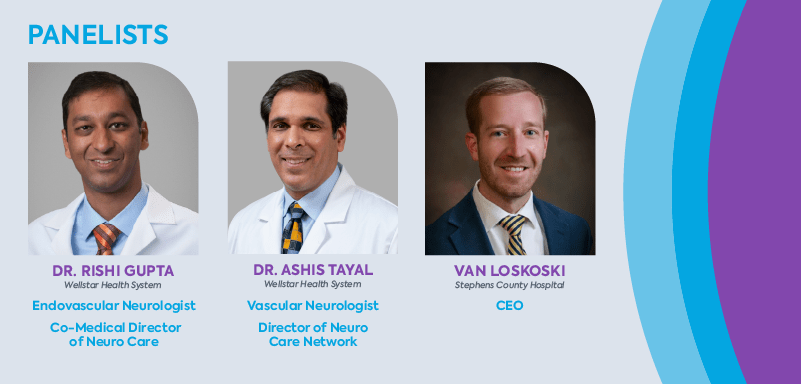

Panelists & moderator

Moderated by David Rubinger, market president and publisher, Atlanta Business Chronicle.

*Wellstar partners with Northwest Georgia Oncology Centers to provide world class cancer care close to home.

Research & treatment

David Rubinger: Where are we today in the world of scientific research? Are we in a good place in terms of research dollars?

Kimberly Jackson: I think we’re in a good place, but we can always be doing better and that’s a fact. There’s no other nongovernmental, nonprofit organization in the United States that’s focused on finding the cause and cures for cancer like the American Cancer Society. We’re committed to continuously funding the best new and ongoing projects at institutions across the country. For instance, right now in Georgia, we are currently funding eight research multi-year grants that are totaling more than $6.3 million. In addition to funding and conducting research, we are mobilizing our grassroot network advocates to increase the funding for cancer research. We’re primarily supporting those investigators that are early in their career, who are doing the most innovative cancer discovery research.

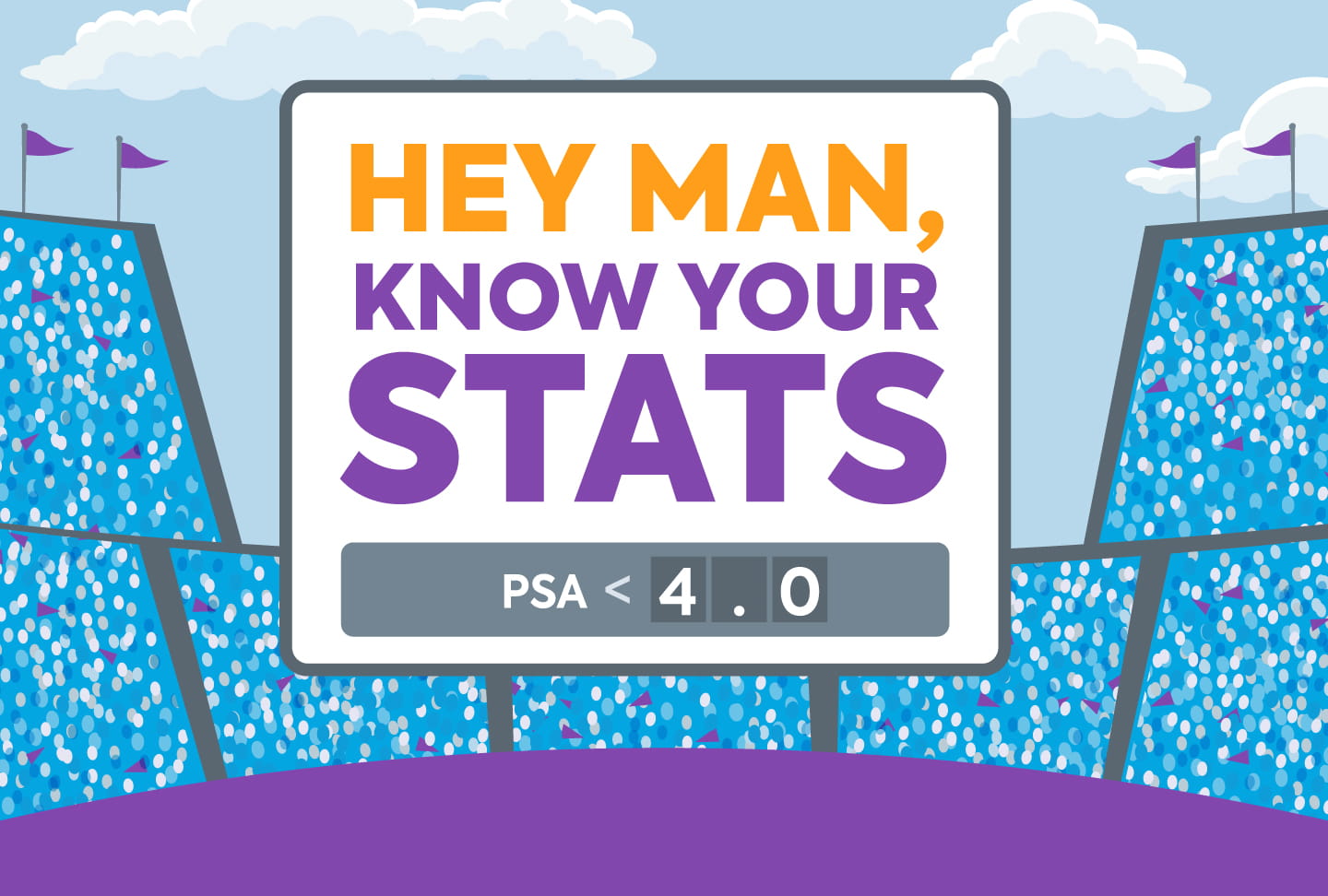

Rubinger: While the aging population is causing the cancer deaths to increase, the average death rate for the population has actually decreased. What do you attribute recent successes to and how will we continue to fight cancer deaths in the future?

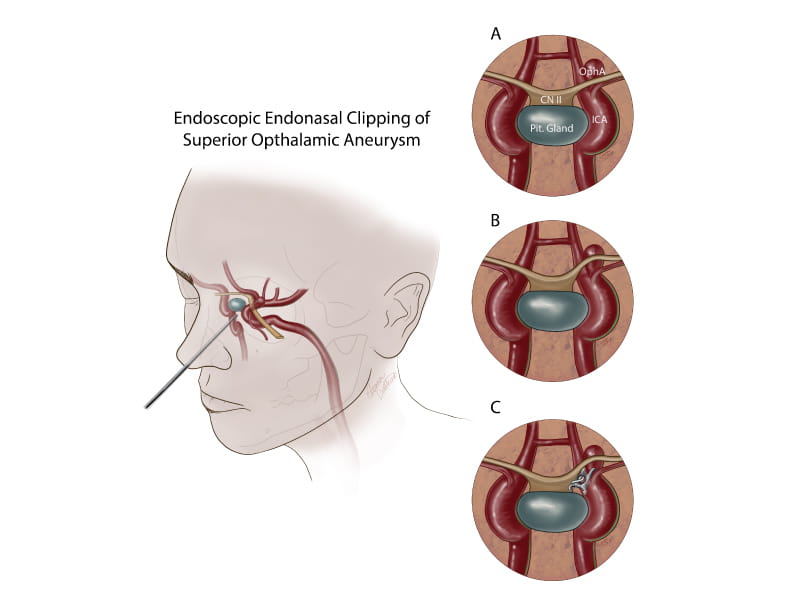

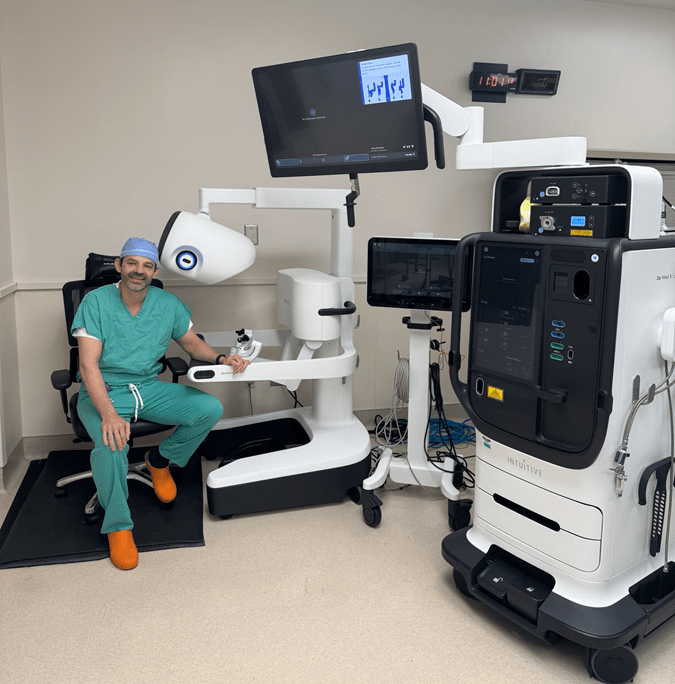

Dr. Steve McCune: The mission of the Wellstar and Northwest Georgia Oncology Centers partnership is to help cancer patients live longer by providing innovative therapies in their local communities. What we have seen in the last 10 years has revolutionized the treatment of certain cancers, particularly lung cancer and melanoma, with immunotherapy and targeted therapies, oral drugs that address a gene mutation. What may be a good way to think of that is it’s the Achilles heel for certain cancers: they have one gene that drives their growth. And there are, because of the research that has occurred, typically one or more drugs that may specifically treat that mutation and block it so that it no longer encourages the growth of cancer cells.

Next-generation sequencing makes it very easy and fast to sequence 400 to 500 genes in a tumor from an individual patient, so that you know exactly any gene mutations in that particular tumor. It’s the most individualized medicine you could have. That’s the reality and that’s very accessible for many patients.

Rubinger: Nicole, from the nursing standpoint on the front line with patients, how has immunotherapy changed the relationship between the patient and the healthcare provider psychologically?

Nicole Centers: From the patient care perspective, it’s very clear that patients are more involved in their care. They want to have more say in their care. When we can educate patients appropriately up front about all of their different options and their care along with their providers, they feel like they have more control. We know when patients feel more in control of their care, they’re more compliant to the plan of care. When it comes to immunotherapy and monoclonal antibodies that are given, they’re generally tolerated far better than chemotherapies of the past. That doesn’t mean everything can be treated with an immunotherapy or monoclonal antibody. However, when we have more options to give patients that they can tolerate better, then it kind of alleviates all of those nightmares of, “This is a horrific journey,” and, “It’s not going to work for me.” Overall, we have medicines that work with your body to fight the cancer in ways that we just haven’t had before.

Patient care & partnerships

Rubinger: The cancer “moonshot" is a term that excited everyone. Have you seen the concept of patient care change from when you first got into the field to where it is today?

McCune: I think it’s dramatically different. In some ways the moon shot has already happened and I'll explain what I mean by that.

Immunotherapy revolutionized the treatment of cancer. If you have a chemotherapy that kills 99% of cancer cells, well that means eventually that 1% keeps coming back. Immunotherapy can work for years, even after the actual immunotherapy has stopped. It’s not a vaccine, but it works in much the same way that a person’s own immune system actually can control or eliminate the cancer. I think that, in a sense, was the biggest game changer for the way that people were treated.

I started doing this about 20 years ago. And so most things that we treated were chemotherapy, very few things that were actually what we would have called targeted therapy or intelligently designed targeted therapy. The first drug was really coming out at that time called Gleevec, which treated CML (chronic myeloid leukemia.) I treated patients before that era who had to have a bone marrow transplant or they were basically going to die of CML. And now we think of CML as a condition that’s almost 100% survivable. We have eight different medicines that are commercially available for treating CML. It’s totally changed the future for some patients who would have had very poor outcomes otherwise.

Melanoma used to be very difficult to treat. Chemotherapy didn't work well. A treatment called Interleukin-2 worked for about 8% of patients and no one really knew why. It basically is an early immunotherapy but with a lot of toxicity. Now you have drugs like Opdivo, Yervoy, Keytruda, which are really the standard of care. Chemotherapy is rarely, if ever, used for melanoma.

There are antibody drug conjugates — something that basically has a payload on the monoclonal antibody, so it homes in on certain proteins on the outside of different cancer cells. That’s a way of delivering a toxin directly to the cancer cells with less impact on normal tissues.

There are companies all over the United States, from large to small, that are really driving the innovation in targeted therapies, antibody drug conjugates, so it’s an exciting time in oncology.

Wellstar has participated in trials for 15 years. In just the last three years, we have participated in cancer trials resulting in over 20 FDA approvals for either new medicines or new combinations of medicines. Usually, it is four to five years before something is FDA-approved. Now not everything’s approved, not everything works better, but it gives people hope and it gives them the chance to have cutting-edge therapies in their local communities.

Rubinger: Nicole, how have advances like these changed the psychology of talking with a patient with a cancer diagnosis?

Centers: I think it has changed. When I started in this field 20 years ago, we would say “the breast cancer down the hall" or “this is the breast cancer treatment.” Now we say, “the patient with breast cancer,” “the patient with lung cancer,” and we treat it as an illness that is part of the whole person, versus the whole person being the illness. That’s a different way that we think about things and that’s how we approach our patients differently when it comes to nursing.

There’s a very unique field inside of nursing called navigation. And one of the things that moonshot really promoted was something that we've been out here doing for a pretty good while, but it brought it to the center stage for all Americans to hear this word called a navigator. It meant someone that was going to guide you on your cancer journey. Several years ago, there was just one kind of navigator and they tried to do the whole care path, but we at Wellstar recognize that there’s lots of pieces to people who could have cancer, people who are being tested for cancer, and those patients that actually have cancer. So we have screening navigators, we have diagnostic navigators, and we have actual care trajectory navigators, which are oncology nurse navigators. We have over 15 of those in our system and some of those specialize by tumor type and some of those are more generalized.

What they do is they actually bring the whole person into view during their care. It means if you have childcare or if you have your parents, that you're taking care of first, or that transportation is an issue, these navigators work with you and your provider as well as your payers, whether it’s insurance or if you don't have insurance, we try and get you on insurance — to be sure that those things that would affect your compliance to the plan of care, they're helping you resolve.

It’s great if you can come in for your treatment. But if your dog has to be walked at two o'clock every single day and your treatment starts at noon, then we need to help you get a dog walker. We need to help you link to resources. For years there have been resources out there that patients didn't even know to utilize. And so organizations have this money that’s sitting there trying to help patients, but no one to link them to it. Navigators link patients to community resources, to national resources. The American Cancer Society has this really great program that will offer patients free rides to go get their cancer care, and most patients don't even know about that. But you talk to the navigator and they're like, “Wait, I have them on speed dial” because they get to know what those resources are, and they can help patients keep their appointments and keep a total life balance.

When we look at that, what that does is it makes their care more effective because they're more compliant to the plan of care.

The other thing navigators do is to help timeliness of care. So if two providers talk and say “we're both going to go see Sally Sue,” or whoever your patient is, and they turn to the front desk and say, “be sure we get this patient on the schedule.” However, the front office staff may not be aware the appointment doesn't meet the latest benchmark for timely care. So what a nurse navigator does is say, “Wait, we have some timeliness to care parameters that we know are best practice.” And they work with that provider or that office to help expedite those appointments.

The best part of navigation is it really brought care back into the patient’s community. Patients didn't understand what was available to them in their community. They thought you had to go to an academic center in a large city that cost them lots of money because they had to stay in hotels or take a flight or go get a car, because there’s so many patients in the states that don't have valid transportation that can take them two hours away. Navigators help patients understand what’s available in their community and the care that they can receive. They can also link them to clinical trials, arrange for assisted lodging and help patients get the best care out there to survive their cancer.

We've also seen an uptick in clinical trials because the navigators say, “Do you remember when your doctor talked to you about clinical trials? Do we want to circle back on that? And do you want to go talk to your doctor again?" They're reinforcing that education.

Second opinions & local care

Rubinger: Let’s move to another topic: the second opinion. The second opinion might be local, but if you have the resources, it might be at Sloan Kettering, MD Anderson or Mayo. Is there less of that going on today because local providers are able to provide that level of confidence in what the care is going to be? Twenty years ago you would have maybe run to Houston.

McCune: I think people still do, but maybe for a different reason. I think they have more information and more knowledge and they're not just running to Houston, they're running to a specialist in Houston or New York or Atlanta. I say, “Hey, you're not stepping on my toes. I want you to get a second opinion. I can help you get that, more than just a cold phone call. Let me try to get you to the right person.”

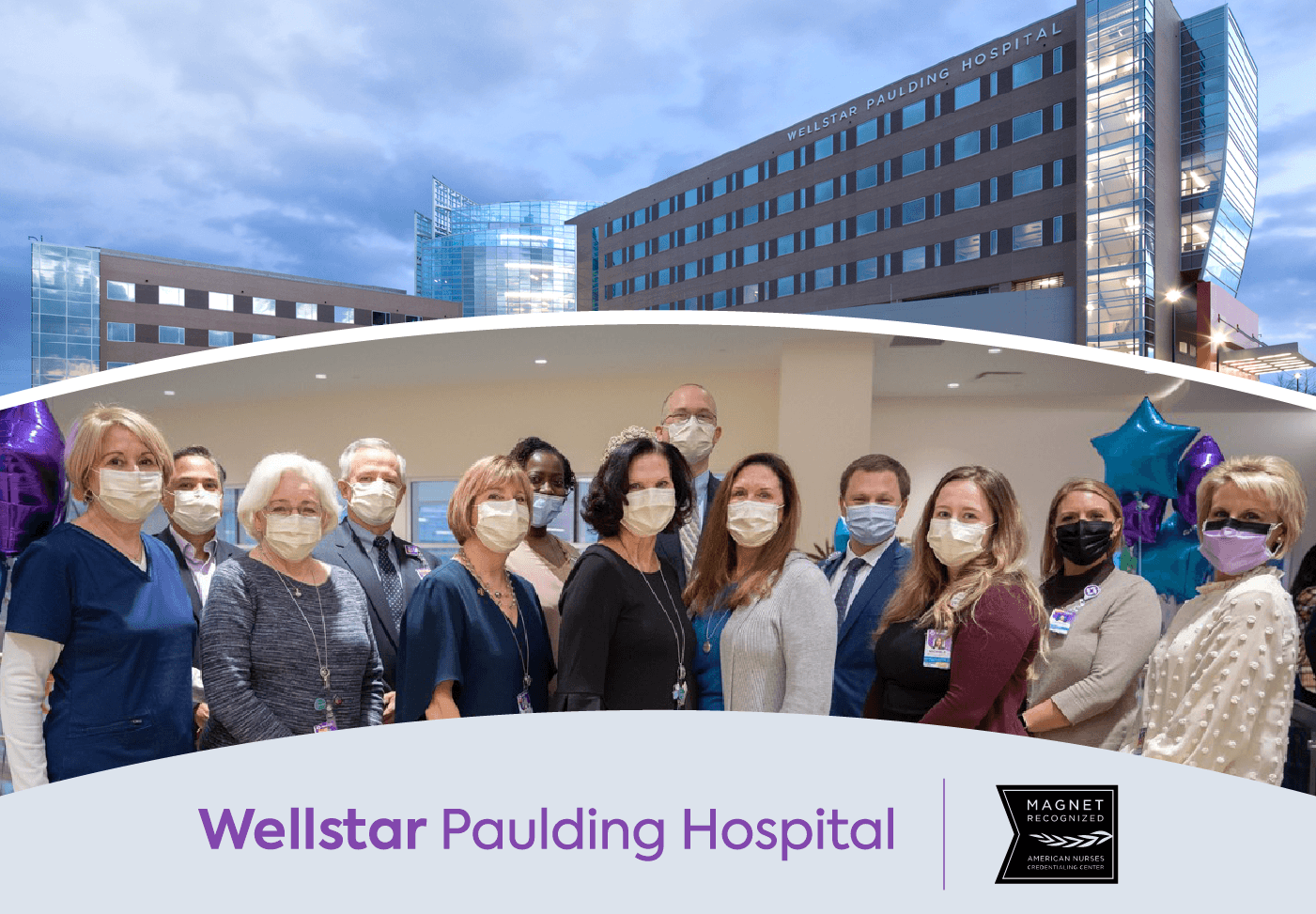

At Wellstar, we do have Mayo Clinic Care Network e-consults available. That’s a pretty easy way to get a quick question answered if we need a specific answer or a second opinion without someone having to travel somewhere.

In addition to second opinions, we believe in collaborative care. We have groups of cancer experts who diagnose and plan treatments together in tumor boards so patients have the best outcomes. In Specialty Teams & Treatments (STAT) Clinics, multiple cancer specialists meet with the patients and their families in one place on one day to help them get questions answered. This helps them start treatment faster so they have better outcomes.

Centers: At Wellstar, 300 cancer specialists in our network can collaborate with each other. When they do request second opinion e-consults from the Mayo Clinic, it is free to patients which is a really nice thing because they usually have to pay for second opinions.

Rubinger: Kimberly, when I think of the Cancer Society, I think of the research dollars going to help cure cancer. But as we were talking earlier about how it helps with driving patients to treatment, the society’s partnerships with a Wellstar or other healthcare systems may be less well known. Can you address that?

Jackson: Collaboration is absolutely critical. So many cancer patients and their families are facing barriers and challenges that are too complex for just one organization to address on its own. To help overcome those barriers, we unite organizations in partnership to improve the lives of people facing cancer.

One example, we have Hope Lodges all over the country where individuals and a family member are able to stay for free and they're wonderful. It’s a great resource for our patients and their families.

Another example is we partner with Wellstar and other health systems in Georgia to provide those transportation grants that Nicole talked about and service to people who need it the most.

For some people with cancer, transportation is a challenge and it creates that barrier to receiving the treatment that they need. Many of them need daily or weekly treatment and often over the course of several months and the need was particularly pronounced during the pandemic. We were able to provide funding to 251 health systems across the country to alleviate that financial burden of transportation.

Another way we mobilize the cancer community on both the national and the local level is through our mission-critical roundtables. We're providing organizational leadership and expert support to multi-organizational roundtables focused on breast, cervical, colorectal and lung cancer, HPV vaccination and patient navigation. Each roundtable has a shared vision to support people to prevent and support and survive cancer. It’s a proven model close to home. Wellstar Health System was a key partner in launching our Georgia Lung Cancer Roundtable, whose primary goal is to improve screening rates and lung cancer outcomes.

Rubinger: Our society has come a long way in terms of reducing smoking. What are the trends in lung cancer that you're seeing? Does it primarily impact your older patients or is it across the age spectrum?

McCune: It can be any age and certainly there are people who are non-smokers who are much more likely to have a lung cancer that is driven by a single gene mutation and those are usually treatable with targeted therapy, which is typically an oral drug. So, in one sense, lung cancer is a disease of people who have smoked for a long time, 30 or 40 years. But it’s also a disease of nonsmokers. I do think people are generally smoking less. I remember people used to smoke in the pediatrician’s office when I was little. Things have changed dramatically.

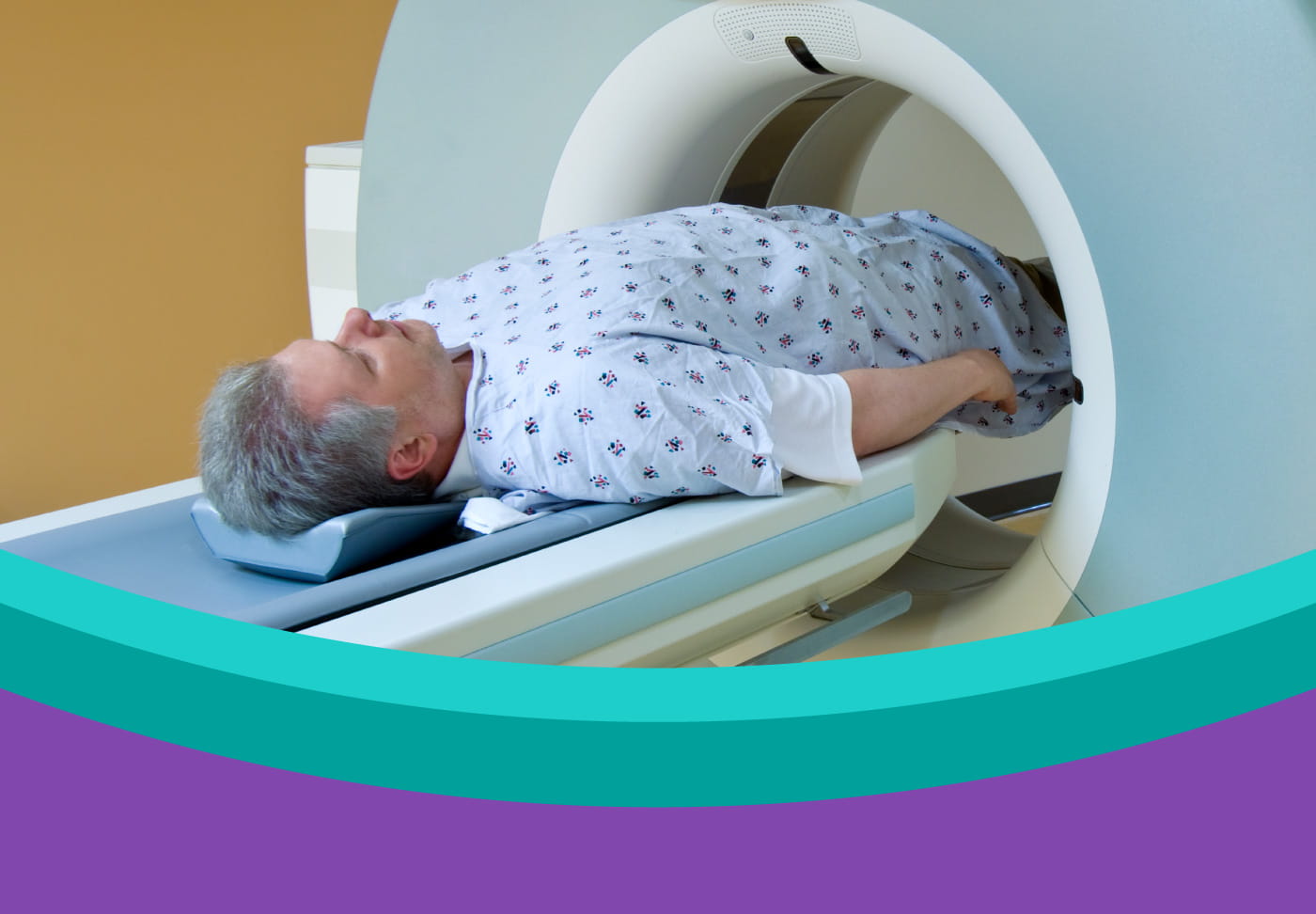

There is a very active lung cancer screening program at Wellstar through the thoracic surgeons and the pulmonary physicians. It looks at people who have had some smoking history, who are typically at more risk for developing lung cancer. They'll have a low-dose screening CT scan, and we do see a number of lung cancers get discovered earlier. That’s a worthwhile initiative when something is surgically curable, as opposed to it’s gotten so advanced that people are having symptoms.

The pandemic impact – screenings & DEI

Rubinger: During the pandemic, I didn't see my doctors as often. None of us did. It was harder to access healthcare the way we did before. What has that done?

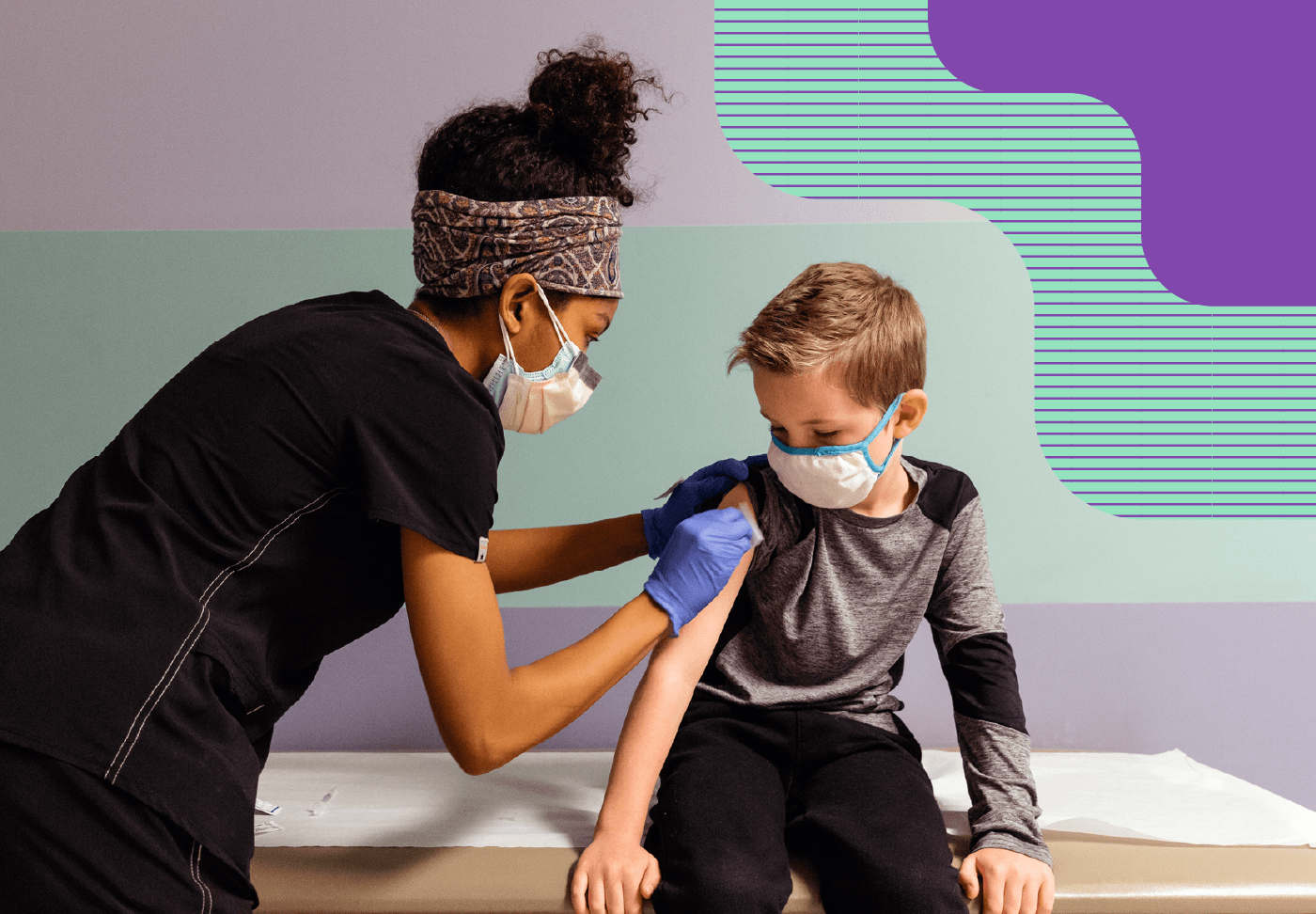

Centers: The pandemic did change us. A lot of screening procedures at the beginning of the pandemic were paused, but we were still able to quickly to return to those services. But the temporary delay made some patients think that screening wasn't as important as it once was. We really worked hard to get the message out there about the importance of early detection.

We use a lot of automated tools like our lung nodule software to help us identify nodules in patients who come into our system for other reasons and have those incidental findings. We also work with our church network here at Wellstar. We work with BLKHLTH in Atlanta, and there’s lots of healthcare organizations that are reaching out to their communities to get people back to screening.

We at Wellstar have made a very concerted effort to go back out and say, “We have kit testing that you don't have to come into the hospital to have done. You can do that at home. Let us help you get the kits.” We reopened our screening mammography centers with all the safety protocols in place. And then we called the patients and said, “Hey, you missed your cancer screening.”

We did see an initial dip because if you're not screening, you're not finding it, as cancer usually doesn't hurt. So most people don't know that there’s something in there growing. Now we're seeing patients come in with later stages, or more advanced tumors than we traditionally would have seen. That’s because of the lag in screening.

Rubinger: Kimberly, is this consistent with what you've been seeing?

Jackson: Yes it is. Early during the pandemic, cancer screening rates decreased dramatically and an estimated 35% of Americans missed routine cancer screening due to Covid-19-related fears and care disruptions when many facilities reduced or suspended services. Screening rates remain below historical averages. In addition to the coronavirus, top barriers to screening are that individuals have no symptoms, procrastination, lack of recommendation, cost, and no insurance. During the pandemic we worked with healthcare systems to address the issue as part of the “Get Screened” initiative. Through donor support, we were able to provide $2.2 million in grant funding to 77 health partners to implement quality improvement strategies to rapidly increase cancer screening rates and reduce the barriers that have been exacerbated through the pandemic. Wellstar was one of our partnering health systems in the Get Screened initiative. They were able to increase their breast cancer screening rate by 6.8 percentage points, which resulted in over 44,000 people in Georgia being up to date with their breast cancer screenings.

Rubinger: One of the crises in our society is the ability that people have to access care. When you think about those things from the DE&I perspective, where do we see the biggest challenges and where are the biggest opportunities?

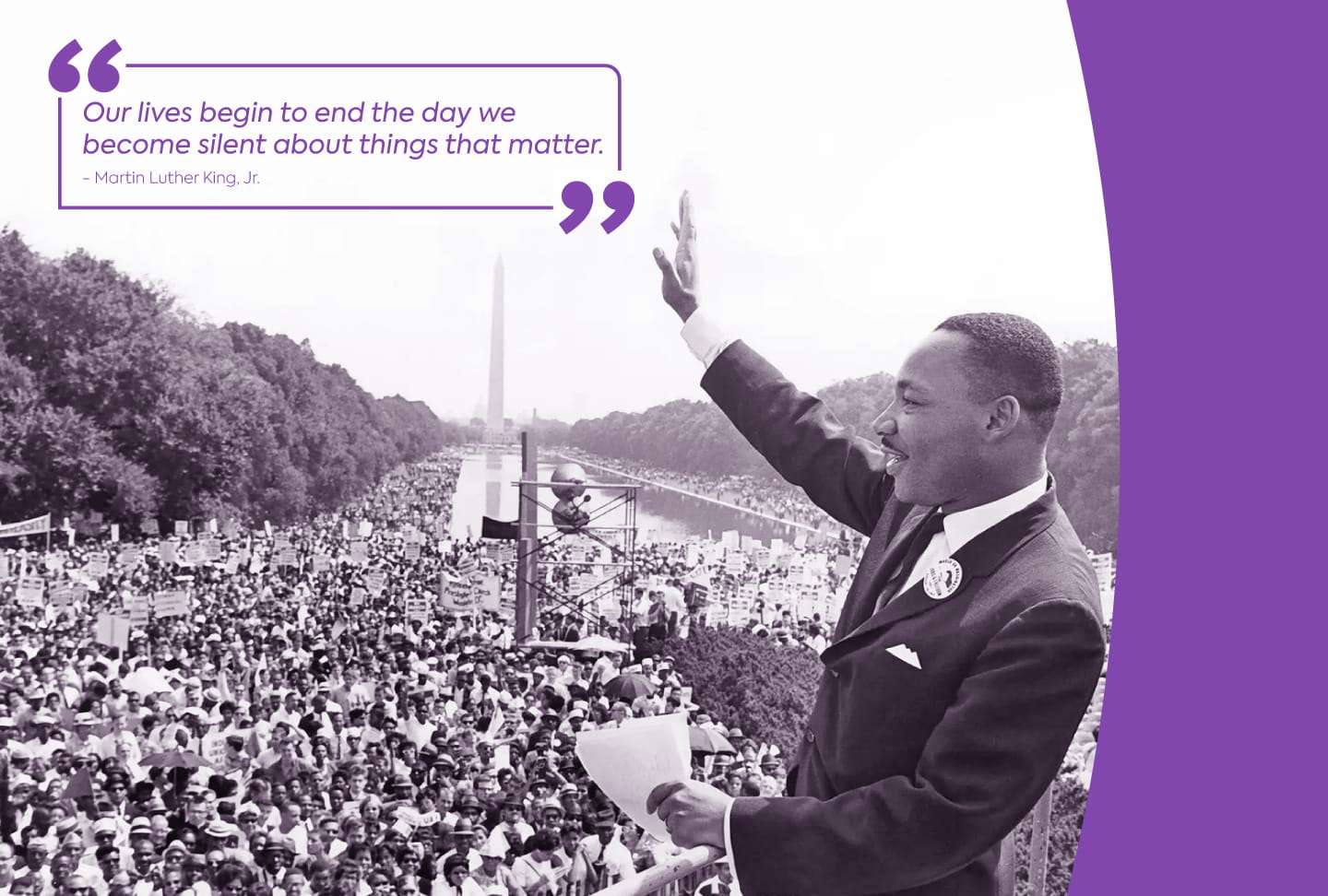

Jackson: While the pandemic is shining a light on the issue, the reality is if we were focusing on having more diverse physicians, nurses, etcetera, if we were focused more on removing the barriers and investing more, we would have fewer people who are getting diagnosed at later stages, or, you know, unfortunately losing their lives to cancer. That’s a fact. There’s an opportunity right now that we cannot shy away from. The evidence is there to show the tie between the impact on an entire community by ensuring equitable health for all by focusing on the ones that need the most is actually equalizing and improving the health of the community itself.

Rubinger: I'm curious what role can the employer play?

Jackson: The employer, they have team members and staff that make up the community that we're seeking to serve. So what they can do immediately is educate the employees on the resources that are available on the prevention side. They can also make prevention a priority and establish norms of only offering healthy snacks, for example.

As well, they can encourage employees to go to their doctors, and also for the top leaders to serve on these boards and these councils of the hospitals and organizations like the American Cancer Society, to be aware and to stay ahead of the issues and to be informed and proactive about helping the community.

Centers: There’s really three ways to look at equitable care, and it’s not a one-path journey. First off, there’s a screening environment and the diagnostic environment, getting people to the services where they are and getting them access to care.

The second part is a mistrust of the healthcare system, which is ingrained in many of our societies across the U.S., so educating them to the safety parameters we have in place to ensure that all patients have equal access to care.

The third component is to teach our healthcare providers, be they nurses, medical assistants, physicians, about diversity and the things that happen to patients who maybe don't look like you, that walk through the door. What we know is, especially among our patients of color, that when they come in, sometimes their complaints aren't taken as seriously as others. We see that in the national studies.

What we have to do is educate our providers and our healthcare workers, but also educate our patients to say “you are your own best advocate.” If you go to a doctor and you're not getting the care that you think that you need or you deserve, then you can go to another place or else you can reach out to your patient advocates at the facility that you're going to. At Wellstar, we have invested a lot of time and energy into educating all staff so that all patients who walk through the door regardless of their social standing, regardless of what they look like, regardless of their history, are all treated equitably, and we do our best.

Rubinger: Dr. McCune, anything to add on that topic?

McCune: Yes. We have a diverse group of research coordinators, both African-American and native Spanish-speaking, so I do think there are opportunities to narrow some of those health gaps. I will say the pandemic across the board affected clinical trial enrollment, because there are typically more procedures like more CT scans that a person has to go through to go on a clinical trial, than just receive what we would call standard of care therapy. So across the board, that is something that has reduced clinical trial participation and that is starting to come back.

But I do think you have to meet people where they are. We obviously have a health system that covers some urban to rural areas in Georgia. One of the things that we're able to do is take clinical trials to people who are as far west as Carrollton, as far north as Cartersville, or closer to the Atlanta area in Marietta, Austell and Douglasville. We're expanding that research network as well.

Not everybody can drive two hours. Not everybody has a family member who can drive them when they're too sick. Access to care is a huge list of things that don't sound like much but a ride to the doctor’s office, a ride to a CT scan is the difference between someone getting care or not getting care. It’s things that seem little but are really not.

When you were talking about what can corporations do, I'll just say, it seems like most people’s experience is very dependent on whether the human resources person is nice to them. From the patient’s point of view, either “they're working with me and I can show up,” or “if I have a bad day, I can just stay home,” or “they fired me yesterday.” So maybe just a little bit of grace there. People have their federally mandated leave but they need more than that. They need a little attitude of caring or just going the extra mile, to help somebody get through their cancer treatment. They'll probably be a better employee and grateful if you treat them nicely.

.jpg?rev=0c641d247be3492db97099991e0fef7f)

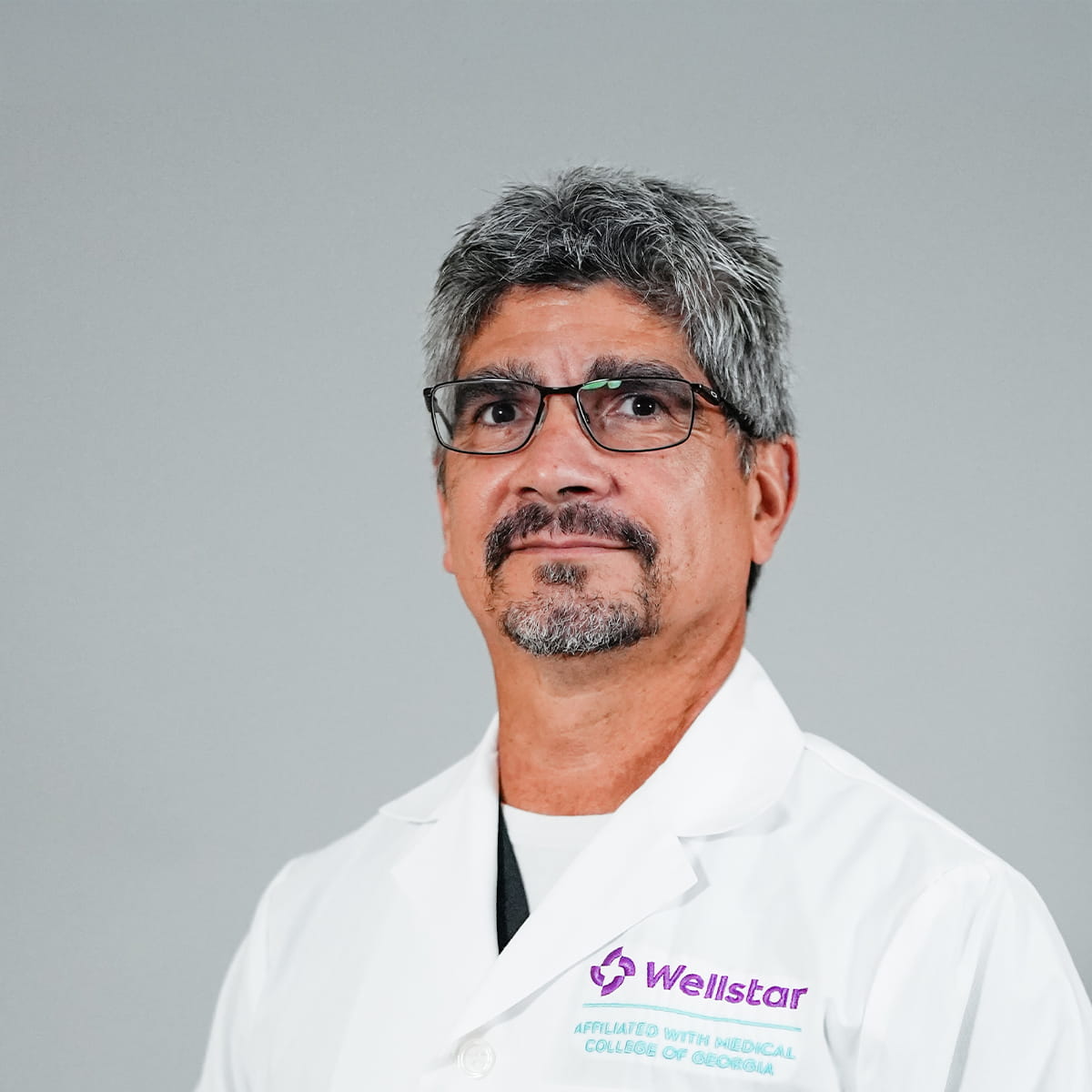

“MCG Neurosurgery has been here for many years and we have a long tradition of teaching and research,” said

“MCG Neurosurgery has been here for many years and we have a long tradition of teaching and research,” said

.jpg?la=en-us&h=300&w=600&rev=d03cbe6dd3c84cd280a26cf59efa223e)

.jpg?rev=e623251622ee4116956d7bf55a43cffe)

.jpg?rev=e49b00e4e51e434aaf29b244ed69b74b)