Advanced treatments

Rubinger: Dr. Gupta, we were talking about more of the preventive side of things, but you get to work in the advanced treatment area. It is amazing what’s happened in my lifetime. When you have a stroke patient and treat them quickly, is recovery more possible now than in the past? What are the advanced treatments that make you feel good about the work you do?

Dr. Rishi Gupta: We’re in the heart of what’s called the stroke belt, where the prevalence of stroke is very high and the population presenting to the emergency room is also younger. It’s unfortunate to see the impact on younger families when the patient may be the sole source of income for the family. The toll it takes financially, physically and emotionally is tremendous. It’s important to understand the impact, stress and burden families feel after their loved one suffers a stroke.

When Ashis and I were in training, we were discouraged from going into stroke treatment because we were told all we would be able to do is give the patient an aspirin a day and send them to rehab.

Now, the range of treatments is much broader and more effective. Treatments have exponentially increased. And the fact that stroke fell to the fifth leading cause of death from the third in a decade speaks to the effectiveness of these treatments. We are absolutely making a dent in stroke death and injury.

One exciting development is the ability to emulate what cardiologists have been doing for the heart without open heart surgery. Now we’re able to insert tiny catheters into the femoral artery, which is a small artery in the leg, and trace it with X-rays up through the body to the brain to remove blood clots.

As of 2015, that treatment has been shown to be highly effective at reducing not only mortality, but disability. Almost 50% of patients who get that treatment can return to a normal functioning life.

Before, that number was closer to 20%. That’s an astounding achievement for stroke care.

The second thing is not only going after big clots but being able to go after small clots. That’s another subset of the population we can now treat which we couldn’t treat before. Catheter-based technologies have been an innovative step forward for our field.

Recently, Wellstar’s Neuro Care team tested a groundbreaking device to treat complex ischemic strokes, working alongside UCLA’s Dr. Jeffrey Saver and device manufacturer Rapid Medical. The technology is called Tigertriever, and it’s adjustable. It allows our specialists to remove the blood clot and restore blood flow with much greater control and precision. The device is now available at hospitals across the United States.

We also helped test a cutting-edge device for treatment called Artemis. Doctors insert a neuroendoscope — a small tube with a camera — into the brain to reach the bleeding in areas that were previously unreachable.

Rural health

Rubinger: You hear about struggles in rural areas when it comes to healthcare. Stephens County Hospital in Toccoa, Ga., is a rural hospital and an example of disparities in healthcare between urban and rural areas. Van, what are the challenges you face in your community when it comes to access to advanced stroke care? And what are the benefits of having doctors like Drs. Gupta and Tayal available to you to help serve your population?

Van Loskoski: Access is the leading challenge for rural healthcare systems.

There’s a significant lack in the availability of highly trained clinical staff, particularly with access to specialty physicians.

Most doctors complete their training in large hospitals in metropolitan areas and remain in that type of setting for the entirety of their careers. There are certainly programs that offer financial incentives for physicians to work in rural areas, typically in the form of student loan forgiveness. But what we often see is that physicians will move to a rural area only for an amount of time required to meet the obligation for that debt forgiveness and they often move back to larger cities.

Rural physicians don’t have as many resources readily available to them as those in larger facilities in urban areas.

It’s also hard for smaller communities like ours to financially support some of these specialists. That isn’t to say the need isn’t there. However, the case volume might be lower, so for stroke services, we aren’t able to support having a team of endovascular neurologists on site. The challenge is finding a way to bring that service here when we need it in a cost-effective manner.

I’m a firm believer that one reason rural community hospitals fail or struggle is that they fail to meet the needs of the community they serve.

So often we see hospitals in rural areas cutting services in efforts to save money, but you can only carve out so much before you’ve eventually carved out your purpose.

Urban-rural hospital partnership

Rubinger: The need for advanced stroke care in rural areas has been proven. I believe a 2020 study published in the American Heart Association Stroke Journal found rural patients with stroke were less likely to receive intravenous thrombolysis or endovascular therapy and had higher in-hospital mortality than their urban counterparts. How have findings like that influenced your decisions at Stephens County Hospital?

Loskoski: We’re focused on the expansion of stroke care in a cost-effective and innovative way. That’s where Dr. Tayal, Dr. Gupta and the rest of the Wellstar team come into play. Telemedicine represents a big opportunity for rural hospitals that haven’t leaned into the utilization of tech in the past. The pandemic propelled us forward in the adoption of telemedicine by clinicians and patients. Now patients are more comfortable using telemedicine, which allowed us to tie into the resources that existed at

Wellstar Kennestone.

That’s something that can really benefit our patients.

Rubinger: Van, before we hop into the details of telemedicine, tell me about how your hospital and Wellstar came together. Did it take a certain degree of salesmanship for you to convince the hospital leadership or the authority that governs your hospital to fall into line with this?

Loskoski: Our board saw the need for us to progress as a system in terms of what services we were offering, and focus on retaining more patients here. I came in with that challenge, the board already having identified that was the direction we needed to take.

The relationship with Wellstar was just as natural. I reached out to a contact at Wellstar and said, “Looking at Toccoa’s population health needs, stroke is really high up on the list.” And he said, “Well, let me just put you in touch with our stroke team.” A month later, I’m meeting Dr. Tayal at

Wellstar Kennestone and he’s saying “We can do this. We are ready and we’re excited.”

It was a really warm reception and we saw the mutual benefit. We were bringing needed services to our community, and Wellstar would be able to utilize their resources to support other Georgia communities.

Rubinger: Dr. Tayal, from your standpoint, what was going on within Wellstar’s world? You saw this opportunity for telemedicine to help expand your reach into these rural communities. How does Wellstar view it and what are the challenges you face when doing this? You may not face any. Tell me about how that whole relationship works.

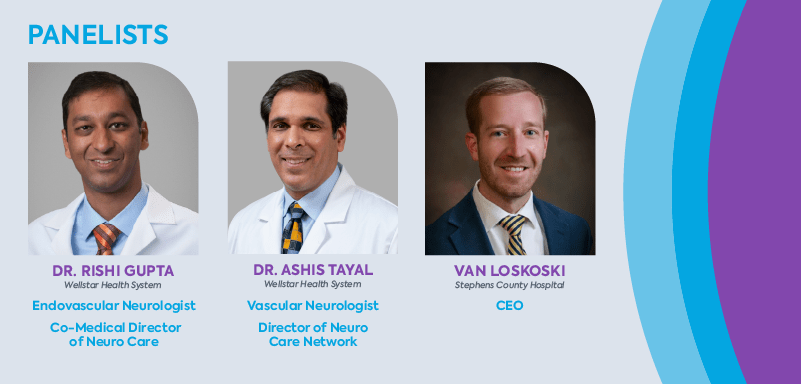

Tayal: There was an opportunity to further develop Wellstar telestroke services with our team of seven vascular neurologists and our network of hospitals. We were able to improve how the telestroke program operates day-to-day so that the telestroke service is highly reliable, consistent and delivers a valuable service to patients.

With the aid of technology, we could evaluate patient symptoms, review brain images and recommend stroke treatment in rural communities and hospitals such as Stephens County Hospital.

So the timing was very good because we had the physicians and we had developed the processes of care.

Rubinger: Walk us through how telestroke actually works. The scenario is, Van’s hospital has a patient who presents with the onset of a stroke. Walk me through the process here. What happens?

Tayal: When a person with suspected stroke within the last 24 hours arrives at Stephens County Hospital — the emergency room physician is connected with the on-call vascular neurologist at Wellstar within 1-2 minutes. The doctors at Wellstar and the physicians at Stephens County Hospital discuss the patient and their symptoms and decide quickly what kind of imaging should be done and which therapies might be appropriate. Then the Wellstar neurologist connects to a video conferencing system — a hardware and software platform that protects patient privacy and is designed to deliver telestroke consults. Virtual meeting software connects us to a video cart in the Stephens County emergency room to communicate directly with the patient, nurse and family members at their bedside.

Rubinger: Is this considered to be the initial triage or does the ER doctor typically have enough baseline knowledge to be able to administer TPA or do something really early on?

Tayal: This is the first evaluation. So, we’re rapidly examining the patient and judging the level of stroke disability and collecting information about their history. Software called Viz.ai allows for an artificial intelligence-driven automated processing of CT brain scan images that rapidly helps us in our decision-making, helps us identify a blood vessel blockage faster, helps us sort out who may be eligible for endovascular treatments. The telestroke provider can then speak to the patient as well as the consultant physician at Stephens County and make decisions about whether the patient is having a stroke or some other condition, whether the patient should receive the clot-busting medication and whether they should be transferred rapidly to another medical center for a more advanced treatment. We address all of the patient’s questions, and we’re trying to do all of this work in less than 20 to 30 minutes. It’s a very rapid workflow.

Rubinger: an, I assume the doctors who are on staff at Stephens, they appreciate that. I would think this gives them the additional tools that they maybe wouldn’t have at their disposal. Or are they like “oh wow, someone is coming in and looking over my shoulder at the work I should be doing?” What is the psychology of your staff?

Loskoski: This is something that we’ve really been asking for, “Give us the specialty support that we need so that we can keep more patients here in our hospital.” If you’re an ER physician or a hospitalist, you really take it personally when you have to transfer a patient to another facility because you know the burden that places on the patient and their family. For many in our community, traveling 45 minutes to an hour away is not a possibility.

I’ve seen it firsthand when it’s such a burden on patients to have their family members travel to visit them while they’re hospitalized. So, every one of our physicians has been extremely supportive and excited about this initiative.

The future of stroke care

Rubinger: r. Gupta, you get to play the role of taking out a crystal ball and talking about the future. It sounds like we’ve made great progress, but that there’s more still to come in terms of trials, devices. We started talking about AI and devices and technologies that are out there. What are the things that get you excited about the future of patient care?

Gupta: We’ve made a big dent in stroke, and I think the part we have not really been able to catch up with is rural health. I believe the future is equalizing outcomes in rural communities to those in metropolitan communities. Step one to make that happen is telestroke.

The most exciting technology is robotics, where we will remotely deliver endovascular catheter-based surgeries in rural communities. It sounds sci-fi today, but one can imagine where a few hospitals in select rural communities are identified as high-volume centers where stroke patients can be transported.

Physicians like Dr. Tayal will evaluate a rural patient through telestroke and alert an endovascular surgeon that this patient has a clot. The patient would go to their local facility’s cath lab and endovascular surgeons would perform remote thrombectomy and remove the clot. In this partnership scenario, the rural hospital would have an endovascular technician. The hospital would not necessarily need a neurointerventional physician on site.

We could do this remotely, understanding that every minute, we’re losing hundreds of thousands of neurons. If we can remove the clot, then you can transfer the patient if necessary.

That sounds crazy in itself. But to take it one step further, consider if EMS now has been tooled with artificial intelligence technology to detect how bad the stroke is. Imagine an application where the first responder’s smartphone takes a picture of the patient’s face, and it says, “that’s a big stroke.” Then EMS can drive just a few miles to a rural facility where that robot exists.

In the next five years, Georgia health experts could set up a road map that would give rural citizens access to the same technology that’s available in metropolitan cities. For me, that’s super exciting.

Rubinger: The American health care system is wonderful in many ways. But we’re a little slow to implement. Where are we in getting there and what’s slowing it down?

Gupta: Physicians need to learn the skill set and get comfortable with the technology. Robotics is a very different skill than using your hands. We’re doing carotid stent procedures which are stents in the neck, as opposed to going into the brain, to refine our skills right now. And the technology from the robotic side of doing brain work is not quite “there” yet. Cardiologists can implant stents in the heart remotely today. India is leading this charge right now. They’ve demonstrated they can safely place stents in the heart remotely from a 30-mile radius.

Another challenge is the 5G network is required so there’s no downtime in the middle of a procedure. But I think the 5G network will be up and working nationwide in the next five years.

Learn more about stroke care at Wellstar.